Written by Brigitte Collins of MacGregor Healthcare, this blog post analyses management and treatment for rectal cancer from a case study of a 48 year old man after his experience with low anterior resection syndrome (LARS).

Progression of treatment for low anterior resection syndrome, inclusive of transanal irrigation (TAI): a case study.

Nearly 43,000 people are diagnosed with bowel cancer every year in the United Kingdom (UK). (1) Of these, approximately 8680 patients will go on to have an anterior resection each year, with 6600 having a stoma. (2) The last decade indicates an increase in the use of sphincter preserving rectal surgery, where a temporary ileostomy is constructed and considered to be standard practice in the UK. (3)(4) Many patients believe that by having this surgery and once the stoma is reversed, bowel function will be back to normal. However, low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) is a possible consequence, which is a myriad of bowel symptoms that include faecal urgency, faecal incontinence, clustering, and incomplete evacuation. It is thought that LARS symptoms are present in up to 80% of patients in the first year after surgery and may persist in 25%. (5)(6) Literature suggests that symptoms can sometimes settle within 12 months, although sources from the National Cancer Strategy, (2) highlight how patients 1–3 years after diagnosis had no, little, or only some control over their bowel function (7).

The following is a case study presentation with history, management/treatment, outcome, and conclusion.

Case presentation

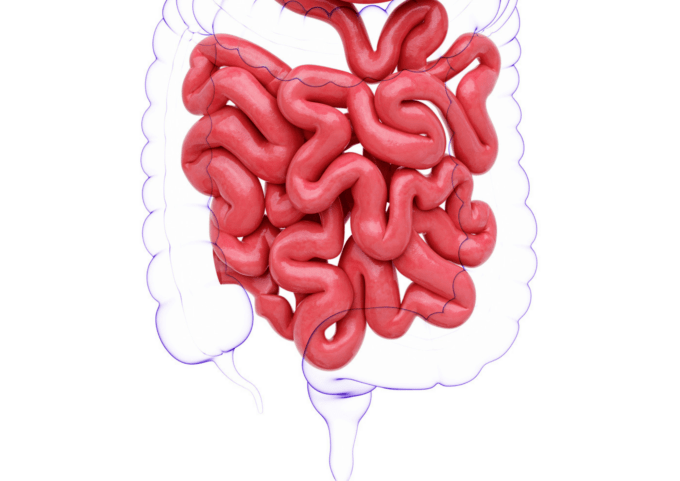

A 48-year-old man (Simon, pseudonym) presented at a colorectal outpatients’ department with red flag bowel symptoms. A colonoscopy was planned under a 2 week wait and carried out where a diagnosis of rectal cancer was given with TNM staging, T3 (the tumour has grown into the outer lining of the bowel wall but has not grown through it), N1a (there are cancer cells in 1 nearby lymph nodes), M0 (the cancer has not spread to other organs). Chemotherapy was given prior to surgery. Surgery pursued with an ultra-low anterior resection (Figure 1) and a temporary ileostomy to allow for protection and healing of the anastomosis.

Fifteen months after initial treatment the ileostomy was reversed with no anastomotic complications. Six weeks following reversal there was a significant amount of loose stool, faecal urgency, faecal incontinence, frequency, incomplete emptying, and clustering, which was identified as having a score of 38 (Major LARS) from the LARS scoring questionnaire (8). National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), (9) recommends that the LARS score be used in assessment.

A referral was made to a nurse led service in a pelvic floor unit to address bowel dysfunction, which was negatively impacting on quality of life, including work, relationships, and mental well-being.

Figure 1

Before surgery

After surgery

Management

Holistic assessment was completed taking into consideration the overall health of the patient, including their physical, psychological, and social wellbeing. This highlights patient’s most important concerns with respect to their bowel dysfunction associated with the patient, thereby allowing therapy to be adapted to the person being treated. Despite the impact that LARS was having on quality of life, the patient’s preference was to address his physical bowel symptoms, as he felt these were impacting his mental health.

Current standard treatments for LARS are focused on symptom relief with therapeutic interventions relying initially on conservative management, which can be summarised into: (10)

- Pelvic floor rehabilitation

- Dietary adjustment/ supplementation

- Pharmacologic agents

This was applied to Simon’s assessment and the following were addressed at his first consultation.

Pelvic floor rehabilitation

Pelvic floor rehabilitation (PFR) is one of the most important treatments for faecal incontinence in general, with success rates of 50–80%. (11) The main objective of pelvic floor rehabilitation is to improve pelvic floor and anal sphincter muscle strength, tone, endurance, and coordination to achieve a positive shift in function with a reduction in symptoms. (12) This can be in the form of pelvic floor exercises (PFE) and/or rectal balloon training. For Simon, PFE were tailored by confirming sphincter activity with digital rectal examination. As a result, a programme was set and tailored to the individual.

Dietary adjustment

Changes in diet usually involve a reduction in insoluble fibres (vegetable, raw fruits), and the avoidance of spicy or stimulating foods/drinks (wine, curries, caffeine), which can worsen diarrhoea, frequency of bowel movements and bloating. (11) A low residue diet may improve stool consistency and therefore reduce frequency of stools (white rice/pasta/mashed potato, chicken). (11) Dietary adjustments had been initiated immediately following stoma reversal, stool became a little less loose, although frequency and passive leakage were a continued problem.

Pharmacologic agents

Consistency of stool can be managed with anti-diarrheal agents like Loperamide capsules. When taken 30 minutes prior to eating, Loperamide can slow down activity in the bowel and can be given as a regular treatment or on an as-required basis. It is advisable to introduce at a low dose and increase until the desired stool consistency is reached. (13) Occasionally Loperamide syrup is considered for doses less than 2mg. (14) Advice was delivered on how taking a regular dose of Loperamide (2mg) can improve Simon’s bowel symptoms.

On a second consultation (6 weeks later), having applied conservative treatment options there continued to be an indication of incomplete emptying and passive leakage. The next treatment to be considered for these symptoms is transanal irrigation.

TAI

A retrospective audit where 15 patients were using TAI to manage symptoms of LARS, concluded that both the frequency of bowel movements and episodes of faecal incontinence reduced. (15) Some of the literature highlights that using TAI in LARS will depend on the severity of symptoms. (16) Other studies show a significant effect of the treatment both in cases of long-term history of LARS following rectal resection (17) and if it is used early as a prophylactic measure (18). There are various TAI systems available, which are divided into low and high-volume irrigation. The process of action for low and high-volume systems recommends that certain types of TAI are better suited for specific symptoms or aetiologies of bowel dysfunction, as set out in the ‘Decision Guide’ (19). The consensus of the group of experts developing the decision guide suggest that cone systems are safer and have never been reported as causing intestinal perforation (20), and as such are especially recommended in patients with LARS when the colonic anastomosis should not be excessively challenged (21). With the use of the decision guide and assessment proforma (21) TAI was prescribed with a low volume approach.

Outcome

One treatment modality alone could not improve LARS symptoms for Simon. Therefore, a multimodal approach was applied with the following treatments established to promote pelvic floor rehabilitation: (22)

- Pelvic floor exercises provided Simon with a better understanding of how to utilise his external sphincter for endurance.

- Stool became a little less loose through dietary modification. Fibres were reinstated slowly, observing for any stool/bowel changes

- Loperamide (2mg) taken each day 30 minutes before breakfast, reduced Simon’s frequency

These treatment modalities relieved some symptoms, although incomplete emptying and passive leakage continued to impede Simon’s quality of life. As a result, TAI was considered and prescribed for use after a bowel movement each morning with the aim of clearing the rectum and preventing faecal incontinence. Adding TAI to his treatment repertoire resolved Simon’s bowel symptoms. Simon recognised that if he did not use TAI the symptoms returned, so he continued with it.

Simon’s bowel symptoms undoubtedly improved and repeating the LARS score (8) gave a total of 10, which demonstrates no LARS. Most psychological concerns were alleviated, although one aspect remained. Simon undertook cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) to reframe and reshape negative thoughts. He continues to apply all treatments and is now living life to the full again.

Conclusion

It is important to recognise that LARS can occur following rectal surgery. This case study covers treatment components required for treating LARS in a patient. A multimodal approach is required to address all symptoms, which may include the need for a psychological support. The overall aim is to ensure that a patient with LARS has the best possible experience of care and improve quality of life.

For free, confidential support and advice on bladder and bowel conditions, contact Bladder & Bowel UK via our website, webform or call 0161 214 4591.

References

- https://www.bowelcanceruk.org.uk/about-bowel-cancer/bowel-cancer/

- england.nhs.uk/cancer/invest/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27582649/

- Powell-Chandler A et al. (2018) Physiotherapy and Anterior Resection Syndrome (PARiS) trial: feasibility study protocol: the PARiS (Physiotherapy and Anterior Resection Syndrome) Trial Management Group. BMJ Open; e021855. doi:10.1136/ bmjopen-2018-021855

- Martellucci J, et al. (2018) Role of transanal irrigation in the treatment of anterior resection syndrome. Tech Coloproctol. 22(7):519-27

- Battersby NJ, et al. (2018) Development and external validation of a nomogram and online tool to predict bowel dysfunction following restorative rectal cancer resection: the POLARS score. Gut. 67(4):688-96

- acpgbi.org.uk/news/anterior-resection-syndrome-collie/

- Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S (2012) Low anterior resection score: development and validation of a symptom-based scoring system for bowel dysfunction after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg, 255(5): 922-8

- https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng151/resources/colorectal-cancer-pdf-66141835244485

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1043148921000488?via%3Dihub

- Fan L, et al (2018) Bowel symptoms and self-care strategies of survivors in the process of restoration after low anterior resection of rectal cancer. BMC Surg. 18 (1): 35

- Rao SS. (2014) Current and emerging treatment options for fecal incontinence. J Clin Gastroenterol. 48(9):752-64

- https://www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/publications/pub-007522

- https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg49/resources/faecal-incontinence-in-adults-management-pdf-975455422405

- Embleton R, Henderson M (2021) Using transanal irrigation in the management of low anterior resection syndrome: a service audit. British Journal of Nursing, 30(21): 1226-1230

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4174224/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28550422/

- Rosen HR, et al. (2019) Randomized clinical trial of prophylactic transanal irrigation versus supportive therapy to prevent symptoms of low anterior resection syndrome after rectal resection. BJS Open. 3(4): 461– 5

- Emmanuel A et al. (2019) Development of a decision guide for transanal irrigation in bowel disorders. Gastrointestinal Nursing, 17(7): 24-30

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26573811/

- Pucciani F et al. (2008) Rehabilitation for fecal incontinence after sphincter saving surgery for rectal cancer: encouraging results. Dis Colon Rectum, 51(10): 1552-8

Comments are closed